There were many facets to my father, and not all of them sparkled. The parts of my dad that glowed didn’t outshine his flaws, but they made the journey with him brighter.

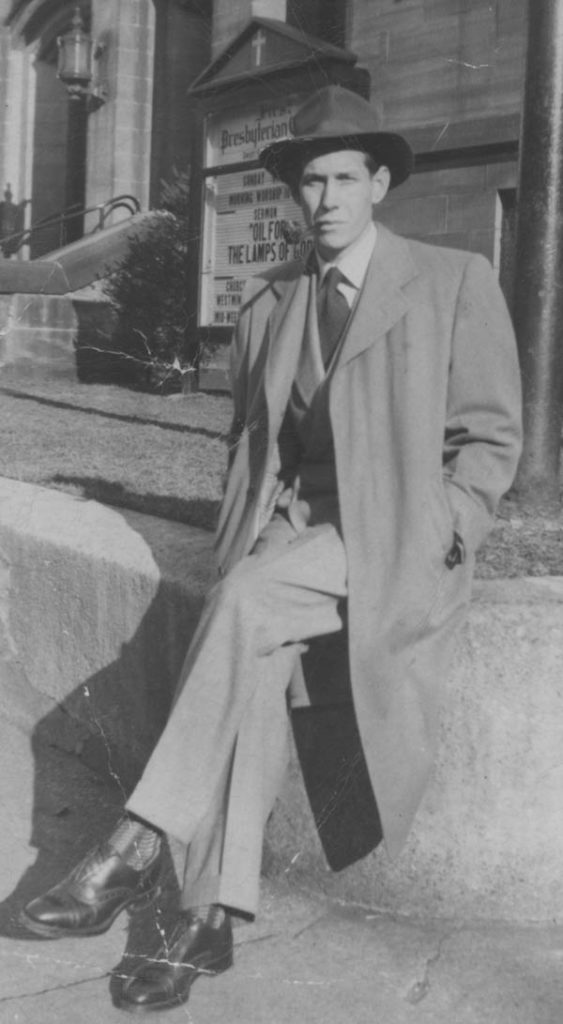

Gene Patterson was born in 1923. He told us stories of his early years, gathering scrap metal for a penny a pound, near-death experiences flying down a long steep road in a homemade soapbox car with no brakes, hoping a car didn’t come through the intersection at the bottom, skinny dipping in the creek with his friends. In the Navy during WWII he got tattoos – a Navy anchor with a swirly ribbon around it and I think a rose with Mother underneath. That faded red and blue ink on his white-gravy skin were enough to keep me from ever getting branded with ink.

He courted and married Momma in Kingsport, Tennessee, and us kids came right away. Both of my parents were stubborn and independent, which may be why he became a union electrician and worked out of town, only coming home for periodic visits. Momma let us run wild, but when he was home he kept a tight ship, and we resented it, except for his first evening home when he often brought us something exotic like white chocolate. Plus he’d always bring his loose change jar full of quarters, dimes, nickels and pennies. I’d sit on the floor and stack them into little paper rolls and got to spend them on anything I wanted – usually candy. I don’t know what he gave to my brother, maybe folding money.

The next day, on Saturday, he’d ask me to go to Kroger’s and get something. I’d protest and want to just go to Kabool’s grocery down the street, but he insisted it had to come from Kroger’s, which was about a mile away. Back then I ran everywhere, so I dashed off, got whatever it was and ran home. I’d burst through the door to our little house, tromp to the kitchen, push the screen door open and look in the backyard – nobody around. I’d run to the bedrooms and see my parent’s door closed. I flung the door open and they’d be scrambling into their clothes. I never could figure out why they were taking a nap in the middle of the day.

Back then kids played outside in each other’s yards or in the street all summer long, so we had many friends. Sometimes my dad would say, “Gather everybody up and I’ll take them to the drive-in.” There’d be big kids and little kids sitting on each other’s laps – this was before seat belts – and he paid our way in and gave everyone money for the concession stand. We watched a movie in the mosquito-infested car that smelled of feet and buttered popcorn, munching Milk Duds, drinking Cokes, squirming, belching and laughing.

One summer we drove to Warrior’s Path State Park and had a rare family outing, a picnic and then a horseback ride. We formed a little train on the narrow horse path around the lake with the leader horse first, my dad next, Momma, my brother, then me. Momma had put on weight, and her bottom looked like two large sacks of potatoes joined together, resting in the middle of the saddle. With each step her poor horse took, gravity pulled the sacks, way over to one side, then they centered again for a brief second before gravity pulled them way over to the other side. Her horse looked like the town drunk on Saturday night, staggering with every step, looking like it might tip over. Momma called back to us, “What are you two laughing at?” which made us laugh even more. I will always be grateful to Dad for giving me that afternoon of entertainment and delight.

He used to take us to the bootlegger’s in a poor part of town called Long Island. To get there we had to drive across a bridge that had steep ramps. We called them ski jumps because Dad waited until no cars were coming, aimed the brown Buick at the bridge and then pressed the gas pedal to the floor. The Buick lunged like a test car on the Bonneville Salt Flats. We’d rocket up the ramp and were airborne; weightless for a few exhilarating seconds before landing with several THUMP thump thumps as the shocks absorbed the impact. At the end of the fifty-foot bridge we’d soar through the air again, completely missing the ramp. We squealed with delight. Dad went into the bootlegger’s little house and came out a couple minutes later with a brown paper sack tucked under his arm. Then we got to fly over the ski jumps again.

I remember a time when I came home from a week at camp, dirty and exhausted, and sat in Dad’s lap, telling him about it. Within minutes I nodded off. As I woke up with his arms around me, felt the warmth of him and breathed in the smell of Old Spice after shave, I felt a mixture of protection and love. He said I’d been asleep for a couple of hours, and he just sat there still, not wanting to disturb me.

As I got older I no longer saw much charm in my father, his trips home became less frequent and I dreaded them because he would impose what I considered unnecessary restrictions on my teenage life. It wasn’t until years later that I started to appreciate him, and in the end we became the best of friends.

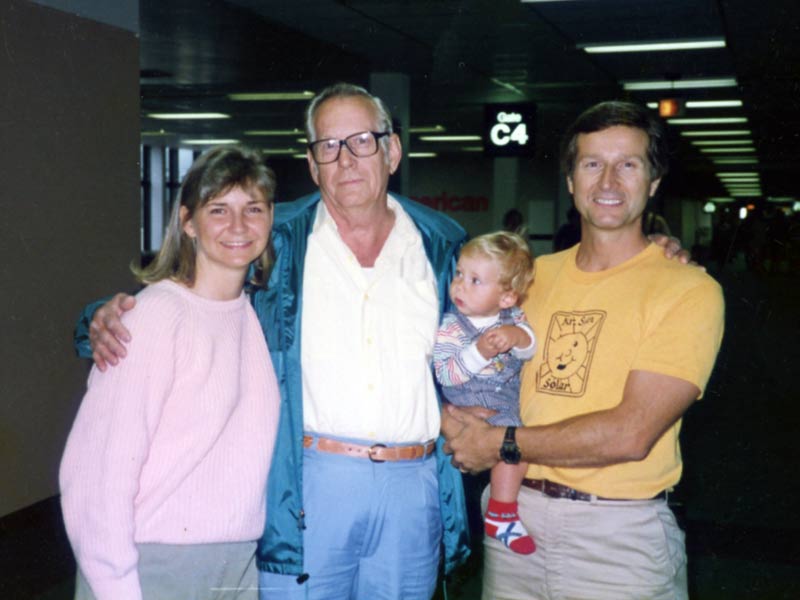

We moved my dad to Oregon the last year of his life. After a lifetime of heavy drinking and reckless living, he needed to be in a nursing home, confined to a wheelchair, with dialysis treatments three times a week. I’d go see him every evening and we’d play simple poker on his bed. My little dog, Shelley – he called her “the grandpuppy” – always stretched herself out in the middle of the game, on top of the cards. I’d move her to the foot of the bed, and she’d work her way back after a few minutes. We both thought it was pretty amusing. We had lots of laughs during the hour or so I was there each evening. I took him to doctor’s appointments, to the beach, out to lunch, sat with him each time he went into the hospital.

I enjoyed his stories about growing up, even though I’d heard them a million times and have forgotten most of them, or never really listened in the first place. He had phrases he used often, like “Let me give you a little illustration,” and “That’s about the size of it.” His expressions were funny but usually off-color, like “She is contrary as cat shit under a couch.” “It’s colder than a well-digger’s ass in the Klondike.” And my favorite although I rarely get to use it, “It’s hotter than a half f—ed fox in a forest fire.”

Sometimes, in quiet moments, he’d start to apologize for not being a good father, and I could see his genuine regret and the pain it caused him, and I usually cut him off with something like, “You did the best you could.” That was true, given his upbringing and circumstances. He could have done more, yes, but he did enough.

On this Father’s Day, I want to thank you, Dad, for your gift of life. After all, I wouldn’t be here if it weren’t for you and Momma. Thanks for teaching us good manners and making sure we went to church on Sunday, even though you never did. The thing I’m most grateful for is your sense of humor. That came partly from Momma, who had a laugh that sparkled like diamonds, but you taught me how to be funny.

You weren’t perfect, but you did the best you could, and there were many good times. I miss you. Happy Father’s Day.

Leave a Reply